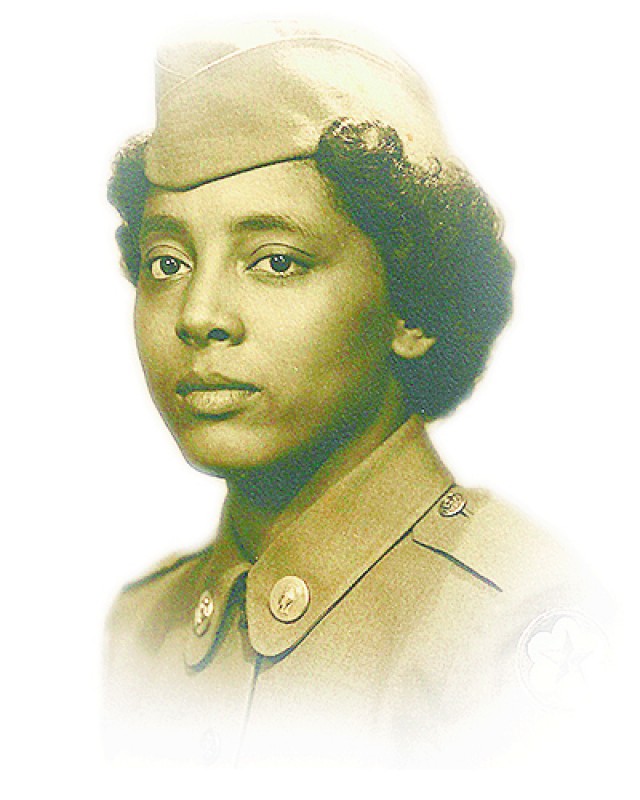

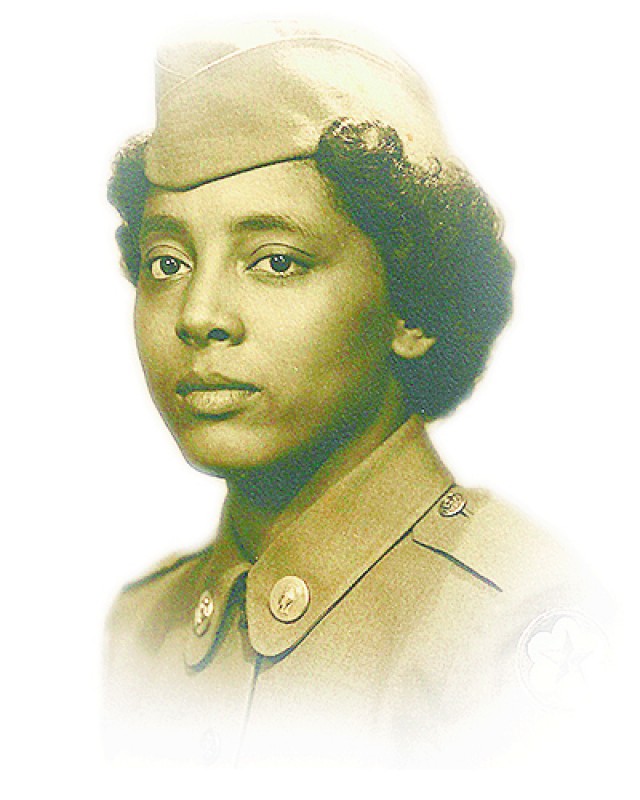

Private First Class Sarah Louise Keys in her Women's Army Corps uniform, 1952

August 1, 1952 - A Soldier Stands Her Ground

Who: Private First Class Sarah Louise Keys, age 22

Service: Women's Army Corps (WAC) at Fort Dix, New Jersey

What Happened: Traveling home to Washington, North Carolina, on leave, dressed in full military uniform

The Incident: At a bus stop in Roanoke Rapids, NC (just after midnight), a new driver ordered her to give up her seat to a white Marine and move to the back of the bus

Her Response: She refused. She knew that on interstate buses, she had the legal right to stay in her seat

📹 Video: The Story of Sarah Keys Evans

Watch this powerful Veterans Day message from the U.S. Army's First Army, featuring Sarah Keys Evans telling her story in her own words at age 92.

[h5p id="131"]

Video length: Approximately 6 minutes | Suitable for grades 3-5 with teacher guidance

What Happened Next

That Night:

- The driver emptied the entire bus

- All other passengers boarded a different bus

- Sarah Keys was left alone on the empty bus

- Two police officers arrested her

- She spent 13 hours in a jail cell so filthy she was afraid to sit down, so she stood all night in her uniform and 1.5-inch heels

- When she asked to call her family, police said they would call—but they never did. Her parents were frantic

The Legal Battle

Sarah Keys initially wanted to forget the whole thing, but her father urged her to fight for what was right. The NAACP connected her with two brilliant young lawyers:

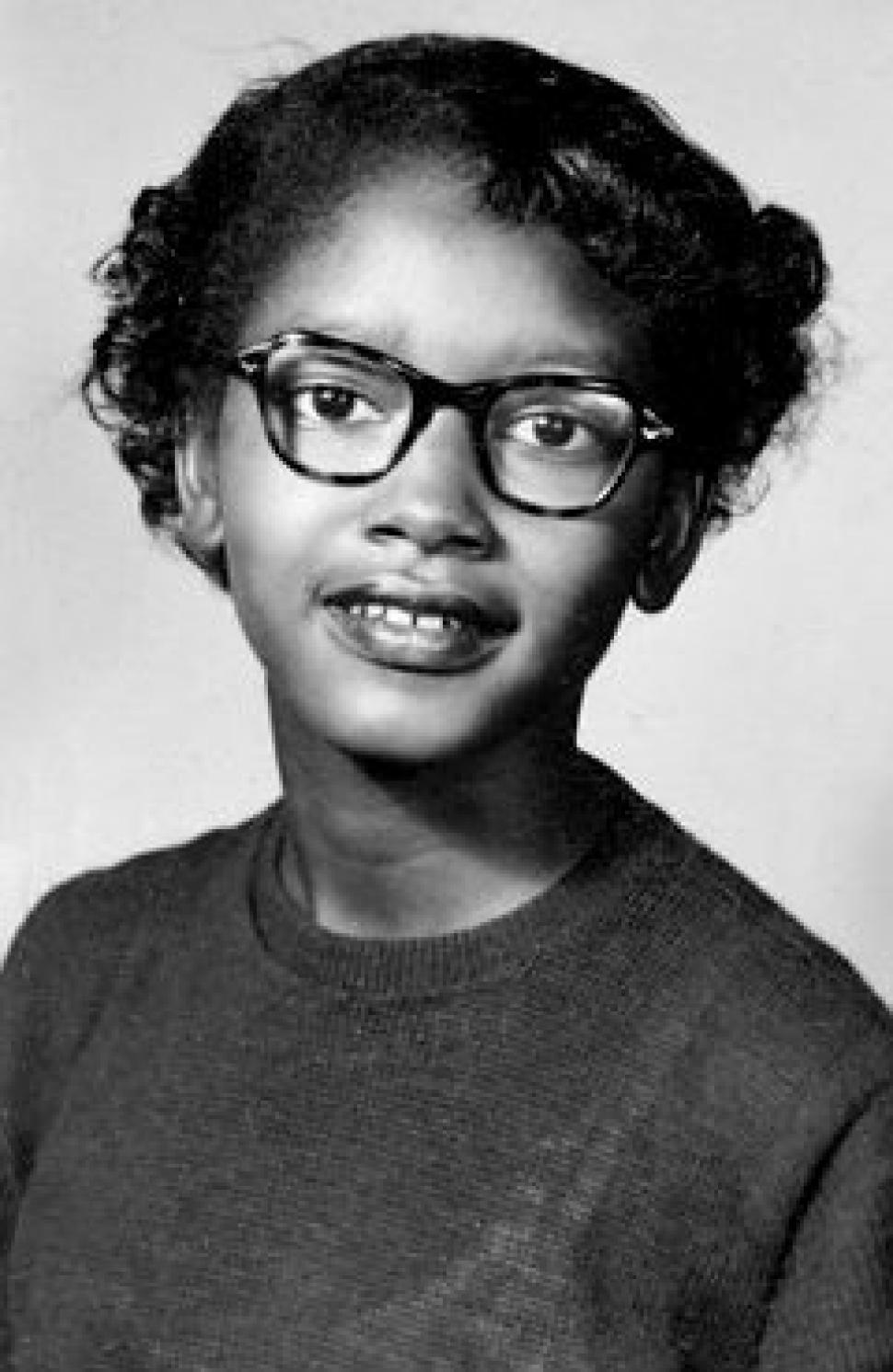

Her Legal Team: Dovey Johnson Roundtree & Julius Winfield Robertson

Dovey Johnson Roundtree was a former WAC officer who had experienced a similar incident in Miami, Florida in 1943. She made Sarah Keys' case her personal mission.

The Strategy: They brought the case before the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), arguing that the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 forbid segregation on buses traveling across state lines.

The Landmark Victory: Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company

November 7, 1955: The ICC ruled in favor of Sarah Keys Evans, declaring:

"We conclude that the assignment of seats in interstate buses, so designated as to imply the inherent inferiority of a traveler solely because of race or color, must be regarded as subjecting the traveler to unjust discrimination, and undue and unreasonable prejudice and disadvantage."

This was the first explicit rejection of "separate but equal" for transportation.

The Problem: Ruling vs. Reality

Sarah Keys won her case—but the ICC didn't enforce it. Southern bus companies continued segregating passengers. It wasn't until the 1961 Freedom Rides—when activists were violently attacked on buses—that the government finally forced bus companies to comply.

Teaching Point: Winning in court doesn't automatically change society. It takes continued activism and pressure to enforce legal victories.

Why We Don't Know Her Name

Despite this historic victory, Sarah Keys Evans chose to stay out of the spotlight. Reliving the traumatic experience became too emotionally exhausting. When author Amy Nathan tried to publish her story in the early 2000s, publishers said they already had books about Rosa Parks, or that Sarah Keys wasn't famous enough.

But her contribution was crucial: Her case provided the legal precedent that made the Freedom Rides possible and helped desegregate interstate bus travel.